hey everyone!

i was in china for a week-and-a-half last month — specifically, chongqing: the southwestern city where my mom grew up and where i spent a good chunk of my childhood. this was, however, my first time going back during chinese new year — and boy did it hit different. it was ten days of eating and driving around and eating and fireworks and going to movie theaters and eating and more eating.

there is, i think, no time when china feels more chinese than during chinese new year. and being there during this most potent and significant time kicked up a lot of thoughts about my own identity and how i think about china. and so — like, i imagine, countless generations of “second-gen chinese american kids who have a worldview-altering trip to china” — i wrote about those thoughts.

enjoy! and for all you chinese americans (or other hyphenated americans) reading this, please don’t be a stranger to the reply box :)

-k

There’s a scene in American Fiction, the new Jeffrey Wright movie, where two brothers (one of whom is gay) chat about their recently deceased father.

Cliff: “I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how dad died not knowing I’m gay.”

Monk: “I think he suspected it”

Cliff: “Mm, he may have. But he didn’t know for sure. He never knew the entirety of me. And now he never will. And that makes me… that makes me real sad.”

Monk: “Well what if he had known and rejected you?”

Cliff: “At least he’d be rejecting the real me.”

The movie is, ostensibly, about the state of race in America; it follows a Black writer who, in an attempt at satire, pens a novel filled with hackneyed and offensive Black stereotypes, only to find that is devoured by the publishing house’s guilt-ridden white liberal audience. This scene, in particular, broadens the focus a bit; I think there’s something here about the idea of “authenticity” — specifically, the way we Americans view it.

In the days before my dad passed away, I grappled with, essentially, the same question that Cliff does. It was unclear if, during those final days in the ICU, he could even hear the words we were saying, and yet, I felt that same urge: that if I didn’t at least try to come out to him then — if I didn’t attempt to share that entirety of me with him in that moment — I would regret it for the rest of my life.

I didn’t end up doing it.

Lack of preparation is at least partly to blame. Cancer is a nefarious killer; the end often comes, to twist the infamous TFIOS quote, “slowly, and then all at once.” Amidst the phone calls and doctor debriefs, there isn’t too much time to consider how one would, for the first time, come out to a family member. (Hey Dad! I’m gay! Blink once for “I love and accept you for who you are!”) But I think another, bigger part of it was that I could not bring myself to put my father — who, for all his love for me and for the world, was born of a different generation — through that emotional distress in his final days.

I feel a certain amount of guilt about having stayed silent. There’s a part of me that understands “authenticity” as a gift in and of itself, as something you owe to the people whom you love, and something that I, in the end, deprived my father of. I find this to be a particularly American sentiment, because “authenticity” is, I think, a trait that Americans place particular value in. American Fiction aside, the moral of many a Hollywood movie is to “be true to yourself;” to be called “genuine” is a relatively high-tier compliment; a 2023 survey found that 90% of American consumers rank “authenticity” as the number one brand quality, over “innovation” or “uniqueness.”

What I ended up doing feels far less like American Fiction and much more like a different film: The Farewell (Lulu Wang’s movie about a family hiding its matriarch’s cancer diagnosis from herself). Specifically, the manifestation of a (Chinese) value system that doesn’t rank authenticity so highly — that subordinates it to other values: filial piety, preserving harmony, absorbing emotional burdens, etc.

This was a moment where I felt, particularly acutely, the pulls of two competing value systems, a moment when my Chinese American identity felt especially bifurcated, when I felt torn between a Chinese and an American way of doing something — neither of which, I think, would have been wrong.

I’ve been thinking a lot, lately, about the broader implications of these varied value systems.

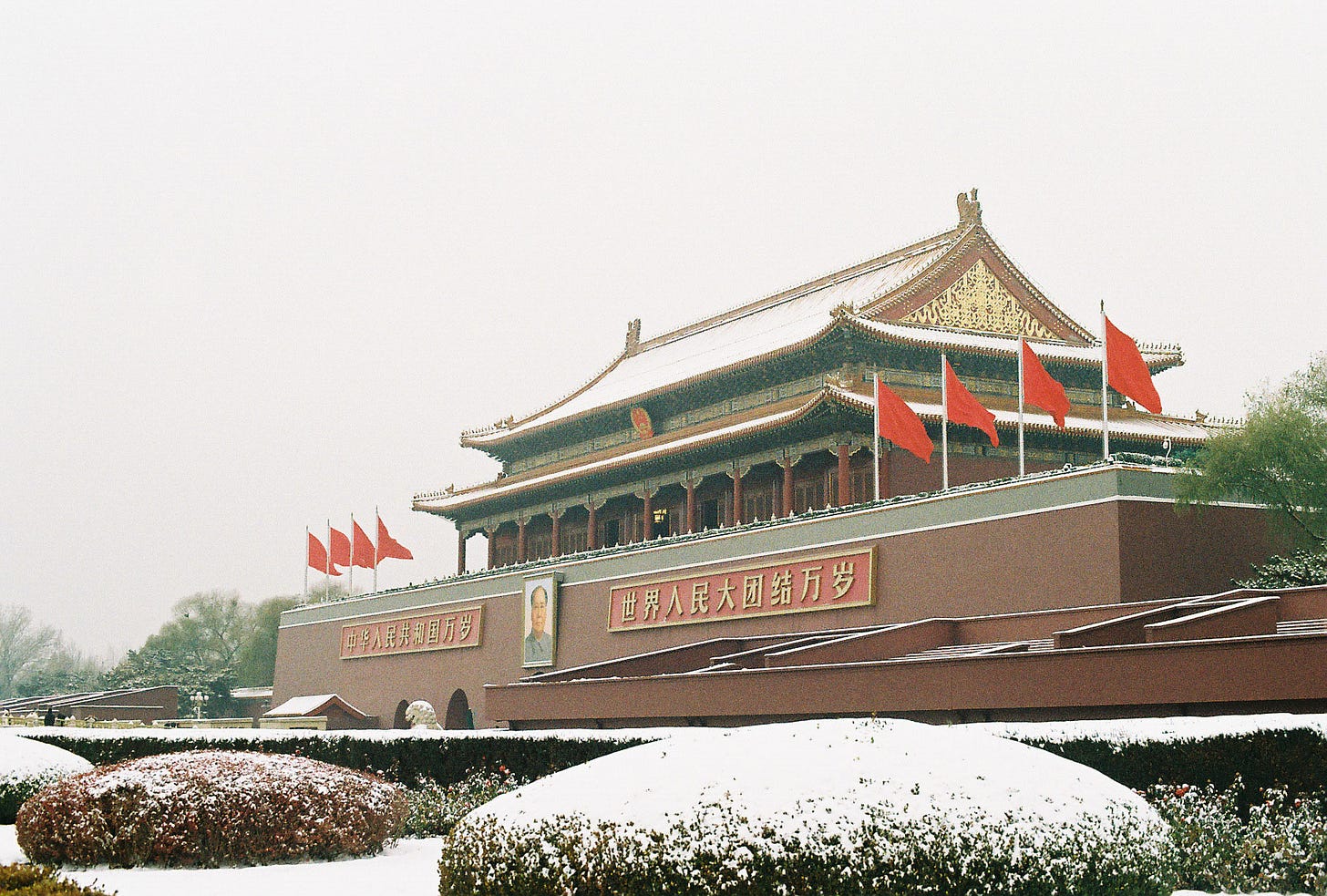

An example: Most Americans find the censorship ubiquitous in China pretty indefensible. For those of you unfamiliar, the Chinese government blocks access to most of the websites that make up our American understanding of the internet (e.g. Google, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Wikipedia), and it routinely takes down or blocks politically sensitive search terms on its domestic equivalents. You’ll find little information on Chinese social media sites about the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, the Uyghur genocide, Hong Kong protests, or criticisms of president Xi Jinping. When I visited China as a teenager, I often found myself looking at my aunts and uncles and cousins scrolling through Weibo (Chinese Twitter) or Douyin (Chinese TikTok) and feeling quite high and mighty about myself — that I was the only one who had seen over the Great Firewall, the only truly enlightened one among them.

But what if the value system changes? What if we swap out “authenticity” from the top spot, and replace it with other values: perhaps “social order” or “improvement of material conditions”? Under such a value system, it might make sense to censor content that could hinder faith in government initiatives or the CCP officials who enact them, especially if doing so allows you to lift over 800 million people out of poverty — an achievement unparalleled in human history, and that China accomplished in, more or less, forty years. One can imagine what America might look like if we adjusted our value system: whether tech conglomerates could be forced to moderate misinformation on their platforms, whether the feedback loop of extreme partisanship might be disrupted, whether Congress might finally be able to pass some god damn legislation.

“Authenticity” is but one example. “Freedom,” “privacy,” and “democracy,” all rank pretty highly on the American value system, and they form the foundation for a lot of why things in America are the way that they are. But, again, what if our value system prioritized different things? Might the bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles, under a government able to seize land from its citizens, finally become a reality? Might millions of lives have been saved in the years of the pandemic, if individual freedoms to not be vaccinated or not wear a mask were curtailed? Might the preposterous number of mass shootings that occur in this country every year finally return to a reasonable number (say, zero?)? The answer, if China is to be taken as an example, is yes.

Now, let’s back up.

To be clear, my argument here is not that the People’s Republic of China is a utopia to be emulated by the nations of the world. I think the pros of freedom of speech outweigh its cons; I think democracy is, generally, a good thing; and I think the absence of these things in China does have serious consequences. On balance (perhaps as a result of my primary school brainwashing), I do think the United States is the best country in the world — particularly because of its diversity, its identity as a nation of immigrants — and if I could choose any country in which to spend the rest of my life, I find it difficult to imagine picking anywhere else.

What I am trying to say is that, in framing the differences between China and the United States not as a battle between good and evil, but rather as a reflection of different value systems, it makes it a little easier to learn from one or the other. It is much easier — as American journalists often do — to paint China as a big, red monster than it is to recognize it as a millennia-old civilization with a value system wholly distinct from America’s: one that produces its share of issues — some of them major — but also its share of potentially valuable lessons about how to treat each other, what a government is capable of doing, or how to build one (1) high-speed railway. (Just one. That’s all I ask.)

This is, I think, a difficult knife’s edge to balance upon. When I extol the cleanliness and safety of Chinese cities to my American friends, I’m dismissed as a CCP loyalist, social credit score supporter, Xi Jinping fanboy, etc. When I bring up Uyghur reeducation camps to my Chinese family members, I’m dismissed as a victim of western media bias, Sinophobia, American exceptionalism, etc.

Such is, I think, one of the great tensions of being Asian American. There is a passage in No-No Boy, John Okada’s 1957 novel about a Japanese American man’s reckoning with his community following World War II, where the protagonist the following imaginary conversation with his mother:

“There was a time that I no longer remember when you used to smile a mother's smile and tell me stories about gallant and fierce warriors who protected their lords with blades of shining steel and about the old woman who found a peach in the stream and took it, and when her husband split it in half, a husky little boy tumbled out to fill their hearts with boundless joy. I was that lad in the peach and you were the old woman and we were Japanese with Japanese feelings and Japanese pride and Japanese thoughts because it was all right then to be Japanese and feel and think all things that Japanese do even if we lived in America. Then there came a time when I was only half Japanese because one is not born in America and raised in America and taught in America and one does not speak and swear and drink and smoke and play and fight and see and hear in America among Americans in American streets and houses without becoming American and loving it.”

There is, I think, a similar feeling at play here. This feeling of being torn between your own self-perception of your cultural past and the hegemonic white gaze that surrounds you in America. W.E.B. DuBois called this “double consciousness,” a concept he wrote about, as it applied to African Americans, in his 1907 book, The Souls of Black Folk:

“After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, – a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

The great anticlimacticism here is that DuBois doesn’t propose any sort of solution to this “two-ness.” The best advice he’s got, it seems, is to “merge his double self into a better and truer self.” Which, despite sounding pretty cool, doesn’t offer much in the way of concrete guidance on whether to come out to your father on his deathbed, or whether government censorship is morally defensible.

The solution for some people, I think, is to just pick a side. For most Chinese Americans, I would argue that it ends up being the American side: to live with an appreciation for Chinese culture and its people — to indulge in mooncakes and dragon dances and osmanthus milk tea with extra boba — but to do so with a fundamental distaste for its contemporary government and political ideologies. This is, I think, the side I’ve lived on for much of my life.

And perhaps it’s all the traveling, all the time away from the USA! USA! USA!, but lately, I find myself increasingly reticent to settle on a side — fighting the inertia and gravitating incrementally toward that middle ground. It is, I think, a hard thing to do; in some ways, impossible. DuBois recognized as much: “He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American.”

Reaching this combined state — being both — has, in many ways, been the mission of immigrant groups since America’s conception. For Asian Americans, a group whose Orientalized other-ness has been particularly hard to shake, it is an especially difficult mission. “The paint on the Asian American label has not dried,” wrote Cathy Park Hong in Minor Feelings. And I think perhaps my way of becoming more comfortable with such a label is to recognize the virtues and vices of China and America for what they are, to reconcile the Chinese and American value systems that I am a product of as best I can, to accept the ambiguity that comes with being Chinese American.

Have a message for Kalos? Wanna say “thank you” or “i feel that” or “i disagree” or “please marry me”? You can do so using the Reply Box below!

this hit hard, especially since I just stayed in china for four months during the fall + visited family during winter break. I've always found it difficult to accept the term 'chinese american' because I never truly felt like I was either but I guess when you're both, you can just have both terms as one as you exist in the in-betweens. really enjoyed this piece nonetheless, it's left me close to tears as I finish my last p-set before spring break in the SEC.